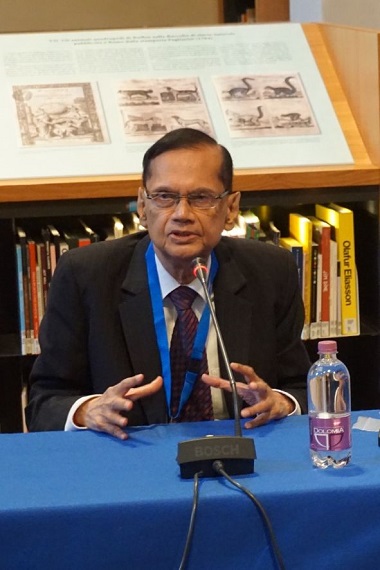

Mr. Chairman, distinguished panelists, ladies, and gentlemen. Both the Maltese Minister and the Rector in their remarks spoke of the interface between religion and foreign policy. There is clearly an interface. The Rector, in her concluding remarks, also used the word ‘cynical’. There's also a great deal of cynicism and skepticism that is a ll too evident, and I think there is a fundamental cause for this. There is the widespread conviction that foreign policy decisions are often made without any regard to ethical or moral factors. It is a question of loyalty to a group to which one happens to belong and then uncritically one follows a course of action that is dictated by that group. There is no attempt to search one's own conscience, decide what is wrong, what is right in a

Mr. Chairman, distinguished panelists, ladies, and gentlemen. Both the Maltese Minister and the Rector in their remarks spoke of the interface between religion and foreign policy. There is clearly an interface. The Rector, in her concluding remarks, also used the word ‘cynical’. There's also a great deal of cynicism and skepticism that is a ll too evident, and I think there is a fundamental cause for this. There is the widespread conviction that foreign policy decisions are often made without any regard to ethical or moral factors. It is a question of loyalty to a group to which one happens to belong and then uncritically one follows a course of action that is dictated by that group. There is no attempt to search one's own conscience, decide what is wrong, what is right in a

particular situation.

Now I think it is worth recalling that there was once upon a time, a very powerful movement called the Non-Aligned Movement. It still exists but it has lost a great deal of the vigor and vitality that it had in the Non-Aligned Movement. And a leader of that period from your part of the world certainly played a pioneering role in that. Joseph Broz Tito of Yugoslavia was one of the pillars of the Non-Aligned Movement. Then also in this part of the world, we had Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus, who played a leading role together with world leaders representing different geographical regions and different cultures. Jawaharlal Nehru of India. Then you are going to have your interfaith dialogue next year in Indonesia. President Sukarno of Indonesia and a leader of my own country, the world's first woman Prime Minister, the late Sirimavo Bandaranaike was very much a part of that movement. There were others whose names are well-known. Nasser of Egypt and so on. Now, the whole point of the Non-Aligned Movement was look at each foreign policy issue on its merits. You don't come to a priori conclusions and membership of a group, fidelity to a group should not be regarded as something that overwrites and supersedes matters pertaining to one's own conscience. Of course, this movement began and flourished in a certain context, the context of a bipolar world.

Now I think it is worth recalling that there was once upon a time, a very powerful movement called the Non-Aligned Movement. It still exists but it has lost a great deal of the vigor and vitality that it had in the Non-Aligned Movement. And a leader of that period from your part of the world certainly played a pioneering role in that. Joseph Broz Tito of Yugoslavia was one of the pillars of the Non-Aligned Movement. Then also in this part of the world, we had Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus, who played a leading role together with world leaders representing different geographical regions and different cultures. Jawaharlal Nehru of India. Then you are going to have your interfaith dialogue next year in Indonesia. President Sukarno of Indonesia and a leader of my own country, the world's first woman Prime Minister, the late Sirimavo Bandaranaike was very much a part of that movement. There were others whose names are well-known. Nasser of Egypt and so on. Now, the whole point of the Non-Aligned Movement was look at each foreign policy issue on its merits. You don't come to a priori conclusions and membership of a group, fidelity to a group should not be regarded as something that overwrites and supersedes matters pertaining to one's own conscience. Of course, this movement began and flourished in a certain context, the context of a bipolar world.

The Rector mentioned the fact that there is no longer any Cold War. I think the Chairman said that there is no longer a Cold War. In some ways it makes life easier. Now the Non-Aligned Movement was developed in the context of a bipolar world. You don't align yourself to this camp or that camp. In one matter, you may agree with this camp, but in another matter, you would completely disagree with that camp and say ‘No! The other camp is right.’ So you preserve for yourselves the freedom of thought and the freedom of action. Now today we live in a unipolar world. There are no longer two warring camps. But that does not mean that the ideology underpinning the Non-Aligned Movement is entirely irrelevant or obsolete. Not at all. I think if you look at the troubled world in which we live, some elements of that philosophy remain very relevant and they have a kind of immediacy today, which they probably did not have in the 1960s when the movement had its heyday.

The Rector mentioned the fact that there is no longer any Cold War. I think the Chairman said that there is no longer a Cold War. In some ways it makes life easier. Now the Non-Aligned Movement was developed in the context of a bipolar world. You don't align yourself to this camp or that camp. In one matter, you may agree with this camp, but in another matter, you would completely disagree with that camp and say ‘No! The other camp is right.’ So you preserve for yourselves the freedom of thought and the freedom of action. Now today we live in a unipolar world. There are no longer two warring camps. But that does not mean that the ideology underpinning the Non-Aligned Movement is entirely irrelevant or obsolete. Not at all. I think if you look at the troubled world in which we live, some elements of that philosophy remain very relevant and they have a kind of immediacy today, which they probably did not have in the 1960s when the movement had its heyday.

So that is a point that I would like to stress to dispel this mood of skepticism and cynicism, to enshrine a state of things in which foreign policy decisions are made according to moral and ethical values. I think that's an important point. Then, reference was made also to the United Nations. The distinguished Foreign Minister of Malta referred to the fact that the UN Charter speaks of freedom from fear, freedom from want.

They are two sides of the same coin. But I think we need to ask ourselves, Mr. Chairman, in a spirit of frankness of candor, whether the United Nations system is functioning today in the manner that was envisaged by the founding fathers. If you look at the seminal documents of the United Nations system - the Charter of the United Nations, the Declaration of Human Rights - are we really behaving in the manner that was envisioned by these sacrosanct instruments? I don't think one could sincerely answer that question in the affirmative.

Today, reference was made to COVID-19 and the responses to that. Look at the Bretton Woods institutions. The Bretton Woods institutions were also fashioned in a certain political context that is the end of the Second World War but the world has changed a great deal since then. But those institutions remain largely as they were. Now the developing world in particular, if the World Bank, for example, were to agree to a policy of debt forgiveness in the excruciatingly difficult circumstances that we have today, then countries that are developing would be able to use their own scarce resources for projects connected with the welfare of their populations. Now take my own country Sri Lanka. We normally earn 4.2 billion dollars a year from tourism. That has come almost to a complete stop. Then our trade relations have been affected. Money coming into the Sri Lankan Treasury from the efforts of our expatriates working abroad in countries like Italy has been affected. So in that situation, if the World Bank were to agree to a policy of debt forgiveness, I think that would greatly accelerate and facilitate the economic development of our countries.

Then look at the composition of the Security Council. Does that in any way reflect the reality of the modern world? It does not. It reflects a certain balance of powers that was only realistic at the conclusion of the Second World War. But today there are other emerging powers. I won't name countries but the entire organization needs to be basically overhauled to bring it in line with contemporary realities. The Economic and Social Council needs to be strengthened. Again, there has to be an emphasis on equality, on human dignity. The whole world, not a section of the world. It is not one section - affluent, powerful, dominating the rest of the world and using the United Nations system as an intrument for their domination. That is what creates a certain lack of confidence in the organs and the structures associated with the United Nations system. So I think these are some of the critical issues, imperative issues that we need to address at this time.

Just a couple of short points. The other one is that any enlightened foreign policy has to be based upon the concept of mature nationhood because foreign policy is in a sense, an extension of domestic policy. So, you know, the country has to be united in formulating foreign policy. You can’t do it in an acrimonious, divided way. Now many of our countries, certainly my own country, we have different parts of the population speaking different languages, professing different religions. Their cultural backgrounds are completely different. That's a problem. Now, how do you work on that? I think the key to that, Mr. Chairman, is the educational system. You know, the young, impressionable minds, certainly in our part of the world, the Indian subcontinent - Sri Lanka, Malaysia, that part of the world - you have different ethnic communities in schools and universities being taught in completely different compartments, and there's hardly any opportunity for young people to get to know each other. Not because there's hostility. There's no hostility at all. It's just that they can't speak to each other. There's no communication possible because of the problem of language. So not only their academic lives but even their cultural and social lives tend to be entirely compartmentalized. Therefore, language plays a key role in communication, a link language for example.

Then the final point I want to make is this that we have to look at ethnic or religious political parties. That is also a critical problem with regard to the formulation of foreign policy and in many of our countries, we have political parties that profess overtly to be ethnic in character and complexion. We represent this ethnic group. We represent this religion. I don't think that's a good idea. It does a great deal of damage. In my own country Muslims, Tamils, members of minority communities have reached the pinnacle of political power and authority as members of the national political parties. National Political Parties! And that has not inhibited their rise within the democratic system. So there is no need for them to detacthemselves from the national polity, to segregate, to compartmentalize the national polity by the formation and the emergence of political groupings that seem sectarian. They have a very narrow perspective, and that is hugely detrimental to the solidarity and the unity of our countries. You are contemplating these matters in the G20 Interfaith Forum. So these are some thoughts that I would like to leave with you, not as concluded by any means, but merely as a basis for a very stimulating discussion that we have under your distinguished chairmanship.

Thank you very much.